ROSE OF MY HEART

First World War letters from a Hubbards boy to the girl he leaves behind

Toronto

(November 1915)

Beloved of all

This is merely a hurried note to say that when next you hear from me, I shall be “somewhere else,” as we leave here at daybreak Thursday morning for England. During the interval between now and the next time I write you, I shall remember you even more than ever before; on my journey overseas I shall bear you constantly in my memory. Now, my darling love, I leave you for a time God love you and care for you until we meet again — this is my most earnest wish for you and, together with my undivided devotion for you, constitutes my parting message. My beloved ideal — farewell! Until, even death

In all true love,

Your Soldier Boy

And so Pte. Lionel Locke Shatford of Hubbards sails for England, leaving behind his beloved Rose Boynton Cary, the young American woman who captured his heart when they met four years earlier. For Lionel, the decision to enlist is as natural and necessary as breathing, and it fulfils his fierce sense of duty and honour.

I far rather that I should lose my life than stand quietly aside and see God’s world and all his noble principles and beautiful ideas perish, he writes to Rose.

He is not alone. Some 619,000 Canadians would eventually enlist with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the war and 424,000 would serve overseas. For Lionel, enlisting brings his plans for a home, a family and a wife to a halt. Rose and Lionel are only just courting and the dark storm that swirls across Europe also sweeps up their dreams, leaving the promise of their future suspended in the cloud of war. Determined not to lose Rose, Lionel writes to her nearly every day, from the ship and the supply camp, from unnamed fields and villages in Belgium and France, from tents and hospital beds.

You are not a dream — nor yet a possibility. Instead, you are a beautiful pure reality whom I adore with all the adoration in my life.

He writes letters of longing and devotion, pledging eternal love, giving voice to the desires of a generation of boys who left home for the front on the cusp of manhood.

Rose, dear, my life has meant so much to me — I have lived, prepared and longed for my supreme day which I had planned was to be a proud and happy one for myself and for Her whoever she should be. . . . My biggest sacrifice will be, if I do not return, I am never to have my own little home, my wife and child.

Theirs is a story of sorrow and joy, faith and doubt. But, most of all, it is a story of love between a boy and the girl he leaves behind.

And now, Rose of my heart, I bid you, for a while — farewell.

With deepest devotion,

Lionel

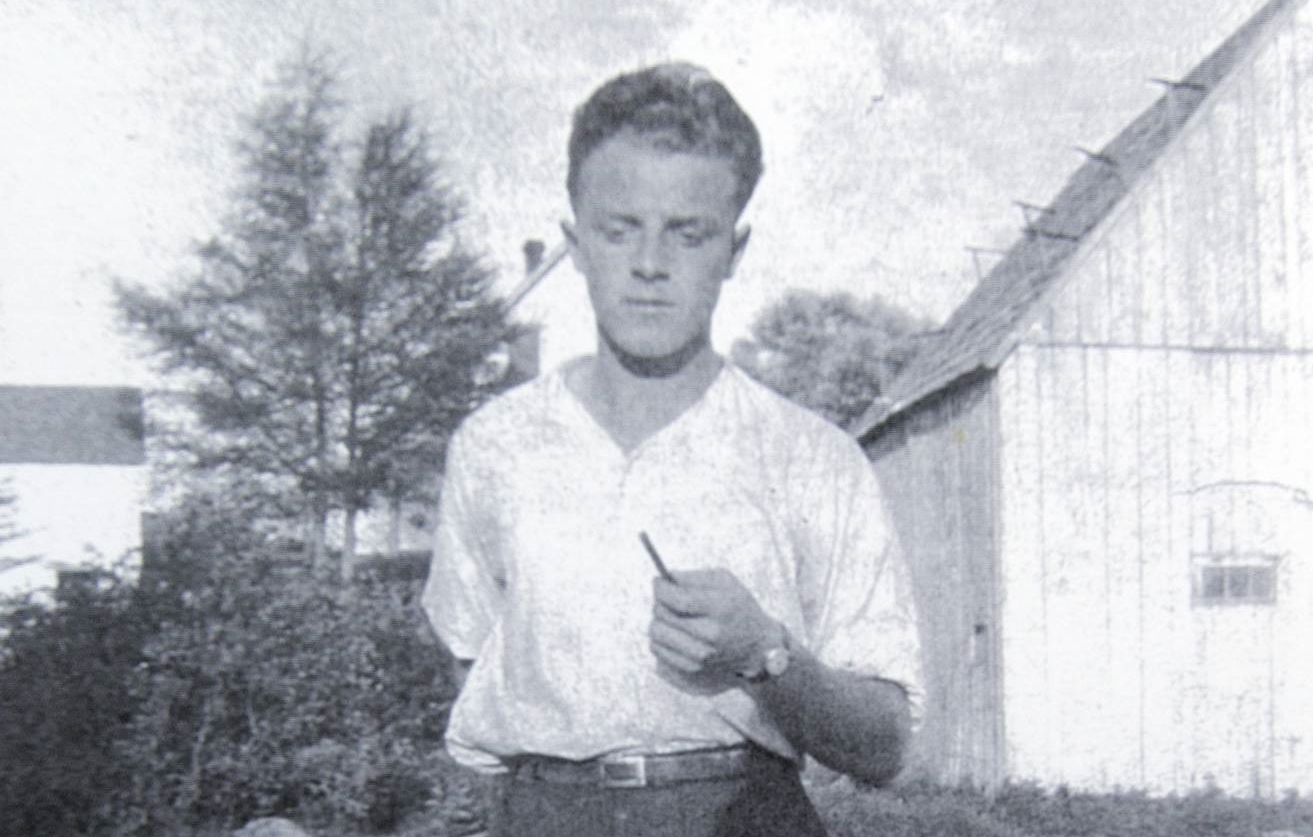

Lionel Shatford spent his childhood summers in Hubbards. Lionel met Rose Boynton Cary in 1911 when the American girl visited for the summer.

THE BEGINNING

Lionel Locke Shatford was born in Halifax in 1894, the eldest son of John Franklin and Harriet Locke Shatford. As a young man, Lionel’s greatest joys are music and nature, and he immerses himself in both, spending as much time as he can outside fishing, hiking, exploring. His family’s cottage, alone on a hill in Hubbards, is simple and homey, the perfect spot to breathe in salty fresh air and to grow strong and sure.

The tiny hamlet of Hubbards has blossomed by the time Lionel is 17 in 1911. By then, the razor-sharp teeth of sawmill blades rip effortlessly through local timber and the freshly milled lumber, piled high on railcars bound for Halifax, bring prosperity — and visitors — to the village. One of those visitors is Rose Boynton Cary, an American music student who arrives with her family to stay at the Gainsborough, an imposing building in the heart of Hubbards. Rose’s father, a world- class sprinter in his college years, brings his family from their home

in Wellesley Hills, Mass., while he attends a conference. Outgoing and outdoorsy, 18-year-old Rose easily fits in with the locals, revelling in new adventures like the night she wanders back to an old hermit’s abode where she has her future told.

When Rose entertains guests at the Gainsborough one evening with a sweet rendition of Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland, Lionel is captivated. Rose and Lionel grow close amid the scent of the sweet bay fern, bonding over their shared passion for music and nature. One Sunday evening, when the summer air betrays just a hint of the coming autumn, they stroll to the old Hubbards bridge, where they sit and talk as day turns to dusk. There, as the old brook tumbles beneath them and their future hangs heavy in the air like a thick Atlantic fog, they share their first kiss.

Lionel and Rose travel together the next day, taking the train to Hali- fax, where the A.W. Perry awaits to take Rose back to her homeland, away from Hubbards and Lionel.

The night of our farewell — my heart was broken. Only God and I know the bitterness of my sorrow then for I was losing not only a friend, but I was losing you.

A letter from Lionel, written in 1917.

FOUR YEARS APART

Dearest,

As I remember you tonight, I recall some words I once heard somewhere, which were like this, I think:

What deed or merit has been mine, What God to me should send

Of all his gifts — the most divine? My other soul — My friend!

Four years ago when it was my sacred privilege to kiss you goodbye in Hubbards, I realized for the very first time what it was to love.

Lionel and Rose split after the summer of 1911, pulled apart by the pressures of life. At home in Massachusetts, Rose finishes her studies at the Boston Conservatory. Lionel heads out west, to Winnipeg and Calgary, partly in search of a career with the Imperial Oil Co.but mostly to escape a Nova Scotia that has become unbearable and lonely. For a while, they correspond, but suddenly Rose’s letters stop, leaving Lionel broken-hearted and bewildered.

By 1914, as Lionel’s isolation deepens, he seeks a transfer to Montreal, where he immerses himself in snowshoeing, swimming, debating and doing baritone solo work at St. James the Apostle Anglican Church. When war is declared, Lionel is in Hubbards and organizes a benefit concert at the Gainsborough. Through it all, Lionel thinks of Rose and carries a photo of her everywhere. Finally, in December 1914, he sends Rose a Christmas card, hoping she will forgive his boldness.

Somehow or other, wherever I went or whatever I did, something always provided that I could not forget you.

And so Rose and Lionel begin again, dancing the slow dance of reac- quaintance, mindful of the distance and time between them. He goes slowly, revealing to Rose small secrets about himself one letter at a time and reassuring her that he has grown into a man of character and strength. “I am five-foot-five and 131 pounds,” he tells her in one letter, “well-built and neither thin nor stout.” By June, Lionel finally finds the courage to tell Rose the feelings he has harboured for four years, using extra-long paper to do so in tiny, perfect cursive writing.

Toronto, Ont. June 20, 1915

Beloved Chum,

. . . Between us — you and me — there is a feeling of genuine love; were this not so, it would have been impossible for either of us to have given expression to such sacred thoughts. . . . In this dream of mine there lies hidden a far bigger possibility than is apparent at first. Oh, Rose of my heart, can’t you see it?

But Canada is at war and for all of Lionel’s optimism and eagerness, the darkness that has been looming on the horizon can no longer be ignored. That April, in their first major battle, Canadian troops face the large-scale use of poison gas and newspaper headlines across the country announce Canada’s intention to have 70,000 troops overseas by Dominion Day. For Lionel, the call can no longer be ignored. In August 1915, at age 21, he enlists in the Ammunition Column of the Army Service Corps.

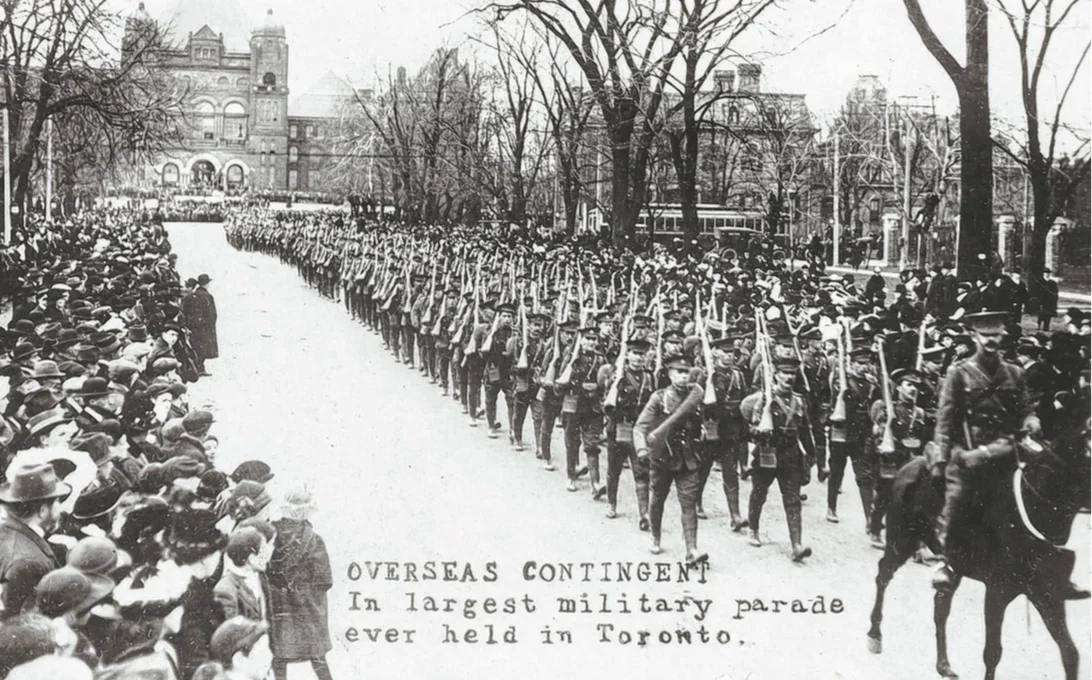

In November 1915, Lionel’s unit leads a procession through the streets of Toronto. (Toronto Public Library)

A SOLDIER IS MADE

Dearest,

. . . I leave tomorrow for the front! At last I shall be put to the test. . . .

My thoughts are mingled and my future uncertain, but my heart is strong and my principles right so I have no fear.

Pte. Lionel Locke Shatford begins training in September 1915 at Camp Niagara, getting equipped as the soldier he now is. Boys and men just like him leave their homes, their jobs, their families to take up the cause, assembling a force never before seen in Canada.

I am huddled on my blankets as I write at this moment; it is long after dark, and it is a typical night in camp. The various battalions are breaking camp and outside I hear at least five or six bands playing different airs, and the troops have built enormous bonfires. . . . Once since I started this letter I stepped outside of my tent to take in the sight. . . . It is hard to see the details because it is night, but impressiveness lies in the effect of the immense fires, the seas of faces about them — the bands playing and the sharp, cold night.

But before he can ship out, he asks to see Rose, desperate to know whether the feelings they once shared still exist — or whether they were just a youthful fancy. Finally, after four years apart, they are together for a few hours, laughing, talking, feeling the distance between them disappear. And then, behind the gate of her hotel in Toronto, they share a kiss that puts all doubt to rest.

And when I had said my good-bye to you and I looked earnestly in your eyes, and saw beyond, even in spite of the mist which befogged my sight — then Rose dear, I knew and understood. Oh, what a glorious afternoon that was! I shall never forget it.

In November 1915, Lionel’s unit leads a procession of nearly 11,000 troops through the streets of Toronto. Two weeks later, he sails for England on the 210-metre Lapland, arriving on Dec. 9, 1915. He is appointed first driver on an armoured truck and begins repeated 645-kilometre night convoys from Plymouth to London. On battle- fields in Belgium and France, war is raging and the need for men is great. By spring, Lionel is at the front.

Somewhere in France,

May 14, 1916

My Dearest Comrade,

. . . Thus far I have endured much and undoubtedly the worst lies still

ahead; Rose, if I see you again — please regard this simple request — never mention or question me regarding my days over here. I want to forget them and let it be blotted out by brighter, cheerier and happier days. . . . When it is over, let the dead past bury its dead. . . . It is dusk now (I can scarcely see) so you will understand why I must kiss you good-night. The stars are just glimmering in — you know — that glorious hour when day — a hot summer’s day — mysteriously loses itself in the cool of a still night; the stars all the while glowing brighter and brighter. I love this hour more than any other in the twenty-four. . . . The guns are booming relentlessly, as in direct contrast to the peaceful Heavens and it makes us wonder why!! Each booming means so many lives, full of possibilities, sacrificed in the cause.

Somewhere in Belgium June 10, 1916

My Own,

. . . Since coming (to the front) and especially during the past three weeks

when I have been driving under shellfire I have experienced my “baptism by fire.” . . . I have already had a few narrow escapes, and saw two of my com- rades fall.

Somewhere in Belgium July 4, 1916

My Dearest,

. . . Of course you have already heard of the Allied victory over here. . . .

Believe me dear, the bombardment was stupendous, and one night while I was “up the line” you could read by the light of the explosions of the guns and star shells.

At the front, along the Somme River in northeastern France, a five- month battle begins that will eventually kill or wound more than 1.2 million men. Six weeks goes by without word from Lionel. And then:

No. 2 Australian General Hospital Boulogne, France August 14, 1916

Dearest,

I realize that my long silence has caused you considerable worrying and

disappointment and for this I am keenly regretful. . . . For some little time, up the line, it had been pretty strenuous and we were “on the go” almost constantly, and the scorching heat was almost unbearable and I began to feel the effects of it, until finally I was taken away in an ambulance.

It takes five weeks for Lionel to recover and return to his unit, and while he is better physically, his letters betray a weariness. Although promoted to the rank of corporal, Lionel is tormented by the thought that he cannot provide adequately for Rose and asks her to carefully consider her future.

Twelve months have passed . . . and still more months lie ahead. You must readily see that from a commercial standpoint I have lost and am losing the most valuable days of my life.

In the field, Lionel’s trucks carry “strange loads; everything from bacon and bread to liquid fire, and from reinforcements to poison gas.” He waits months for a letter from Rose and then, as the late November winds usher in the bitter cold of a coming winter, she replies and fills Lionel with hope and courage.

In the Field December 14, 1916

My dearest Rose,

. . . I come to you to ask that you will accept me as your life-comrade, and

to be allowed to consecrate my life — body and soul to the serving of your happiness and welfare. I want you to openly claim me for your own, throwing aside all uncertainty, doubt and secrecy. . . . You are everything to me dear and I want you to be my wife and the Little Mother of our home.

And then Lionel rolls up in his blanket and awaits Rose’s reply.

LIVING FOR THE FUTURE

My darling Girl,

. . . Ever so many nights as I lie rolled up in my blanket and looking up at

the stars, I see you and as I listen there is a silence even which can be heard it is so still, and then softly, as if from way beyond, I hear your voice crooning, and I see you smile.

As the war to end all wars drags into a third year, mired in the trenches of Belgium and France, Sgt. Lionel Locke Shatford and Rose Boynton Cary become engaged. Their talk turns to the future, planning their lives together. Rose tells Lionel she is filling her hope chest and sewing pillowcases where the two will lay their heads, side by side. When Rose questions Lionel about his religious views, he quotes Robert Green (Bob) Ingersoll, an American Civil War veteran and orator:

“I belong to the great church that holds the world within its starlit aisles; that claims the great and good of every race and clime; that finds with joy the grain of gold in every creed, and floods with love and light the germs of good in every soul.”

He dreams of a child, hoping for a girl with fair hair and blue eyes like his beloved Rose, and they talk of a simple life, filled with music, nature and — always — love.

Days are dark just now, as all days will ever be whilst I am separated from you my own sweet wife-to-be. But as long as there is life, there are brighter days over and beyond, to which my heart’s longing can look for inspiration and comfort.

When America declares war in April 1917 and Rose’s brother, Bill, enlists and joins the ranks of the engineers, Lionel reassures her that Bill is in a good branch of the service and telling Rose that he’s delivered “hundreds and hundreds of tons of material for the engin- eers over here at the front: barbed wire, trench mats, sandbags.”

On the rare night that he has a few leisure hours, Lionel hops on an old Triumph and, under the cover of darkness, races the motorcycle through the countryside, sometimes covering 125 miles a night, eating up roads and hills, as though speed and distance could erase the unending horrors of the front.

By spring of 1918, as Germany launches a series of offensives, Lionel can’t shake a feeling of doom. In April, he narrowly escapes with his life.

A shell burst just inside an old broken down wall alongside of our lorry just as we were going through a deserted village. Well, to make a long story short, that old wall saved us from certain destruction, catching (as it did) all the low fragments of the shell, and we got clear with nothing more than a shower of earth and stones on its way down, after having been blown up.

Then, on May 1, 1918, a letter arrives from a base hospital in France. Lionel has fractured his leg in several places. An exploding shell? Enemy fire? No, the soldier who has survived three years at the front is hurt while on a breakaway during a friendly unit soccer match. Lionel is transferred to England and, for a time, it looks as though will be invalided back to Canada. But in late September, five months after the accident, Lionel is rendered fit for service and sent to Shorncliffe, Kent.

As the Hundred Days campaign rages along the Western Front, Lionel undergoes examinations for his commission, telling Rose he finished at the top of his class. In letters that betray his impatience and weariness, Lionel promises Rose that he is healthy and whole and that they soon will be together.

Shorncliffe October 14, 1918

Sweetheart mine,

I think the long darkness is passing away and I can feel that the brightness of a New Life is near at hand. . . . I will kiss you adieu for a little while. Know always that I am thinking of you, and am ever mindful that I am devotedly & faithfully. Your boy.

A NEW LIFE

Lt. Lionel Locke Shatford married Rose Boynton Cary on Aug. 2, 1919, in Berkeley, Calif. They were married at dusk, a glorious hour, as Lionel once wrote to Rose, when the stars glimmer and glow brighter and day turns to night.

Lionel received his commission just after peace was declared on Nov. 11, 1918, and, ironically it prevented him from sailing home on Dec. 10 as he had been scheduled to do. Instead, as a mechanical transport officer, he stayed behind to serve in the demobilization effort. Lionel arrived back in Halifax in June 1919 and set up in busi- ness with his father. He was finally reunited with Rose at her parents’ home in California on Aug. 1, the day before their wedding and almost four years after they last saw each other.

Rose’s brother Bill suffered shell shock during the war and spent the rest of his life in an institution.

Rose and Lionel lived in Halifax and Hubbards, where they raised a daughter, Harriette, who was a strawberry-blond beauty with blue eyes, just as Lionel had hoped. In 1923, Lionel was diagnosed with diabetes and given three months to live. But pioneering medical care saved his life and, with Rose acting as caregiver, he beat the odds.

A devoted wife who often deferred to her husband, Rose was never- theless known for her spunk and spirit. “She was a tough and gutsy human being,” her grandson, Peter McCreath, wrote at the time of her death. “Quitting wasn’t part of her being. . . . As for nursing homes, they were for old people.”

Lionel and Rose were devoted to each other for 58 years, eventually settling full time in Hubbards near Lionel’s childhood cottage. Lionel died on Jan. 30, 1977; his beloved Rose died on March 17, 1980, at

the age 86. No one knows what happened to the letters Rose wrote

to Lionel; only one complete letter survived. It is dated July 8, without a year, although it appears to have been written in 1916.

My own dearest Lionel —

What a joy it is to mean something to someone and have that someone mean everything to you. You have taught me to know real love as it should be and which never before had I experienced.

Lionel and Rose are buried side by side in a peaceful, sun-dappled cemetery not far from the bridge over the river where, in 1911, they shared their first kiss.

Deborah Clarke

Clothesline Media